Kotlin for Java Developers

> Click here to get the exams code

Kotlin is a general purpose language which supports both functional programming and object-oriented programming paradigms. It's an open-source project developed mainly by JetBrains with the help of the community. Like Java, Kotlin is a statically typed language. However, in Kotlin you can omit the types, and it often looks as concise as some other dynamically-typed languages. Kotlin is safe, it's even safer than Java in terms that, Kotlin compiler can help to prevent even more possible types of errors. One of the main characteristics of Kotlin is its good interoperability with Java. It's hard now to call Java a modern language. However, it has so huge ecosystem, that it would be really difficult to recreate it from scratch if you use a new language

Cool features

- ► There is no

newkeyword. - ► There is no

statickeyword. - ► The keyword

objectis a singleton in Kotlin:object K {fun foo() {}}; K.foo() - ► Type is inferd.

- ► If is an expression, you can assign it to a variable.

- ► There is no ternary operations.

- ► Instead of throwing an exception, we can just call

fail() - ► Smart casting

> Having a class Pet that can be Dog or cat, we can do pet.meow() or pet.woof(), kotlin is going to do the cast for us

- ► Formatting multiline strings

val q = """To code, or not to?""" - ► There are no primitives

- ► Creating regex expressions

1val regex = """\d{2}\.d{2}\.\d{4}"""

2regex.matches("15.02.2016")

- ► Converters like:

"a".toIntOrNull(),"1".toIn(),"1".toDouble(), - ► equals infix

1fun getAnswer() = 42

2getAnswer() eq 42 // true

3getAnswer() eq 43 // false

- ► Infix

toto create Pairs, likeval pair: Pair<Char, Double> = 'a' to 1.0 - ► Mutable Extensions properties

1var StringBuilder.lastChar:Char

2get() = get(length -1)

3set(value:Char) {

4 this.setCharAt(length-1, value)

5}

6

7val sb = StringBuilder("Kotlin")

8sb.lastChar = '!'

9println(sb) // Kotlin!

- ► You need to define a class as

opensometimes because the default of a class isfinal - ► there is no package-private, instead its:

internal - ► We can use

sealedmodifier to restrict class hierarchy

1sealed class Expr

2class Num(val value: Int): Expr()

3class Sum(val left:Expr, val Right: Expr): Expr()

4

5fun eval(e:Expr):Int = when(e) {

6 is Num -> e.value

7 is Sum -> eval(e.left) + eval(e.right)

8}

9

10// withouth the sealed modifier, it would need an else for it doesn't know where all the class inheriting from Expr are.

Data initialization, var, val and const

- ► val: "value" its read-only

- ► var: "variable" its mutable

- ► const: For primitive types and Strings

> about const: It's value is known at compile time, the compiler replaces the constant name everywhere in the code with this value, then it's called a compile-time constant.

We can initialize two variables using a Pair

1fun updateWeather(degrees: Int) {

2 val(description, color) = when {

3 degrees < 10 -> Pair("cold", BLUE)

4 degrees < 25 -> "mild" to ORANGE // same as pair

5 else -> "hot" to RED

6 }

7}

Lists

Kotlin has mutable an imutable lists, such as:

1val mutableList = mutableListOf("java")

2mutableList.add("Kotlin")

3

4val readOnlyList = listOf("Java")

5readOnlyList.add("Kotlin") // <- that doesnt work

Data class

Data modifier has equals, hashCode, to-string, and copy methods.

data class person(val name)

it creates:

- ► Equals

- ► hashCode

- ► toString

we can copy the instance and give the new attributes

1data class Contact(val name:String, val address: String)

2

3contact.copy(address="mew address")

Functions

return void here is of type Unit

We can define 3 types of fuctions

- ► Top level functions

1fun topLevel() = 1

- ► Member function:

1class A {

2 fun member() = 2

3}

- ► Local functions:

1fun other() {

2 fun local() = 3

3}

1fun max(a:Int, b:Int):Int {

2 return if (a>b) a else b

3}

4// that becomes

5fun max(a:Int, b:Int) = if (a>b) a else b

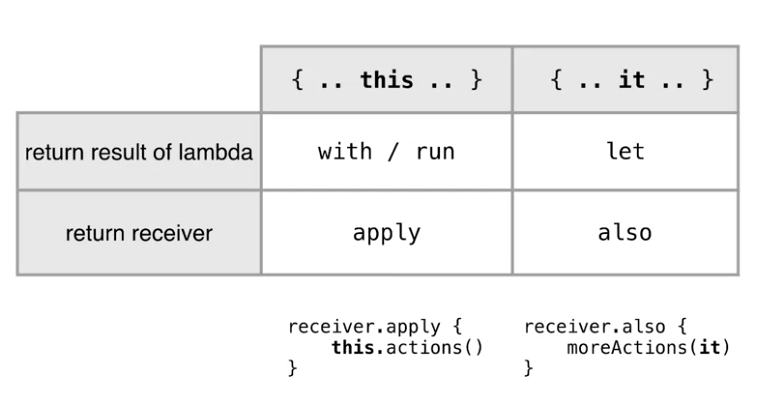

Library functions (run, let, takeIf...)

functions that look like built-in language construct

- ► run: Runs the block of code (lambda) and returns the last expession

1val foo = run{

2 println("calculating")

3 "foo"

4}

- ► let funtion: when you want to pass something as an argument only if it's non-null.

1fun getEmail() : Email?

2val email = getEmail()

3

4if(email != null) sendEmailTo(email)

5// or better

6email?.let {e -> sendEmailTo(e)}

or to functions

1fun analizeUserSession(session:Session) =

2 (session.user as? FacebookUser)?.let {

3 println(it.accountId)

4 }

- ► takeIf: returns the receiver if it satisfies the given predicate or returns null

1issue.takeIf { it.status == FIXED }

2person.patronymicName.takeIf(String::isNotEmpty)

3

4val number = 42

5number.takeIf { it > 10 } // 42

6// if the predicate don't fullfill, it returns null

7

8issues.filter { it.status == OPEN }.takeIf(List<Issue>::isNotEmpty)?.let { println("some are open")}

9

10// filtering

11people.mapNotNull { person -> person.takeIf { it.isPublicProfile }?.name }

- ► takeUnless: is the opposite, takeUnless which returns the receiver if the predicate is not satisfied.

- ► repeat It simply repeats an action for a given number of times.

1repeat(10) { println("Welcome!")}

- ► use: The use function contains all the aforementioned logic of closing the resources in the correct way.

- ► withLock lock the file

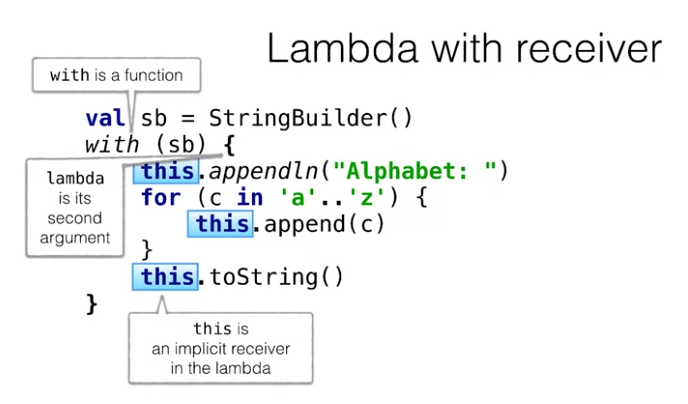

- ► with: You can call all the members and extensions without explicit receiver specification

1val sb = StringBuilder()

2with(sb) {

3 appendln("alphabet: ")

4 for(c in 'a'..'z'){

5 append(c)

6 }

7 toString()

8}

9// or

10with(window) {

11 width = 300

12 height = 200

13 isVisible = true

14}

- ► run, but as an extension makes it possible to use it with a null-able receiver.

1val windowOrNull = windowById["main"]

2windowOrNull?.run {

3 width = 300

4 height = 200

5 isVisible = true

6}

- ► apply: Is the same as with, but Apply is different because it returns the receiver as a result. Its helpfull in a chain.

1val mainWindow = windowById["main"]?.apply {

2 width = 300

3 height = 200

4 isVisible = true

5} ?: return

- ► also: Also is similar to apply, it returns the receiver as well. However, there is the difference that it takes a regular lambda not lambda with a receiver as an argument.

1windowById["main"]?.apply {

2 width = 300

3 height = 200

4 isVisible = true

5}?.also { window -> showWindow(window) }

Default values and positional paramters

we can specify default values for parameters, such as:

1fun display(character: Char = "*", size: Int = 10) {

2 repeat(size) {

3 print(character)

4 }

5}

6

7display('#', 5)

8display('#')

9display()

10// or direct the parameter

11display(size=5)

using the name position we can even change the order.

to call a kotlin function with default values, we need to suply an annotation to the function, like:

1@JvmOverloads

2fun sun(a: Int=0, b: Int=0, c:Int=0)=a+b+c

3

4// java

5sum(1);

Conditionals: If & when

if in kotlin is an expression, there is no ternary operations!

when as a switch

You no longer needs to use break;

1// java

2switch(color) {

3 case BLUE:

4 System.out.printLn("cold");

5 break;

6 default:

7 System.out.printLn("hot");

8}

9

10//kotlin

11when(color) {

12 BLUE -> println("cold")

13 else -> println("hot")

14}

Multiples conditions

when can or not have parameters, so if it doesn't have, i''l check its cases for a boolean expression and evaluate them, so when can be a group of ifs or a switch statement.

to check several conditions, you can specify like:

1fun respondToInput(input:String) = when(input) {

2 "y", "yes" -> "I'm glad you agree"

3 "n", "no" -> "Sorry to hear that"

4 else -> "I don't understand you"

5}

or even comparing sets, the argument is checked for equality with the banch conditions

1when(setOf(c1, c2)){

2 setOf(RED,YELLOW) -> ORANGE

3}

Checking a type

we can use is to check a class type, like if pet is a super class of Cat and Dog we can check like:

1when(pet) {

2 is Cat -> pet.meow()

3 is Dog -> pet.woof()

4}

doing the same as the java instanceof

Loops

The are basicly the same, but:

For loop looks a bit different. First, a different keyword is used to express iteration over something in. Second, where meets the element type.

1var list = listOf("a"."b","c")

2for(s in list) {

3 print(s)

4}

Iterate over a map

1val map = mapOf(1 to "one", 2 to "two", 3 to "three")

2for((key, value) in map) {

3 println("$key = $value")

4}

Iterating over an index

1val list = listOf("a", "b", "c")

2for((index, element) in list.withIndex()) {

3 println("$index: $element")

4}

Iterating over Ranges

instead a forin loop we can use a range

1for(i in 1..9){

2 print(i)

3}

4// -> 123456789

5

6// or until, excluding 9

7for(i in 1 until 9){

8 print(i)

9}

10// -> 12345678

or more complex cases like with a step

1for(i in 0 downTo 1 step 2){

2 print(i)

3}

4// -> 97531

Using in over Ranges

there are 2 ways to use it

- ► Iteration:

for(i in 'a'..'z') - ► Check for belonging:

c in 'a'..'z'

EG, to check if a string is a letter:

1fun isLetter(c:Char) = c in 'a'..'z' || c in 'A'..'Z'

2isLetter('q')// true

3isLetter(*) // false

and it can be used in a when case as well.

> They can even be stored in a variable such as: val intRange:IntRange = 1..9

Using in into collections

in can be used to check if an element is part of a list, in Java that would be like:

1if(list.contains(element)) {}

but in Kotlin we can do as

1if(element in list){...}

Comparables

We can compare anithing that has a compareTo, bein a code like the following

1class MyDate:Comparable<MyDate>

2

3if(myDate.compareTo(startDate) >= 0 && myDate.compareTo(endDate) <= 0) {...}

can be rewrite in kotlin as

1class MyDate:Comparable<MyDate>

2if(myDate >= startDate && myDate <= endDate) {...}

3

4// or even

5

6if(myDate in startDate..endDate){...}

Exceptions

They are very similar to Java with one important difference. Kotlin doesn't differentiate checked and unchecked exceptions. In Kotlin, you may or may not handle any exception, and your function does not need to specify which exception it can throw.

1val percentage =

2 if (number in 0..100)

3 number

4 else

5 throw IllegalArgumentException("wron value: $value")

being then try & catch an expression, being able to be assigned to varialbes, like followingval number = try {Integer.parseInt(string)} catch(e:NumberFormatException) {null}

Extension Functions

Extension function extends the class. It is defined outside of the class but can be called as a regular member to this class.

The general usecase for them is when you have a library and wants to extends its api, or something YOU DON'T HAVE POWER OVER.

1fun String.lastChar() = this.get(this.length -1) //this can be ommited

2

3fun String.lastChar() = get(length -1)

4

5// so we can use as

6"me".lastChar() // -> e

> They are not freely accessible, you need to import them.

Infix

there is a second way to extend a funtion with infix

1infix fun <T> T.eq(other: T) {

2 if (this == other) println("OK")

3 else println("Error: $this != $other")

4}

5

6evaluateGuess("BCDF", "ACEB") eq result

Nullable

The introduction of null to earlier programming languages, is known to be called "billion dollar mistake". Because nulls are ubiquitous, NullPointerExceptions, attempts to dereference null pointers, are very common as an issue

to define:

1val s: String? // nullable

2val s: String // non nullable

Elvis for null values: If we want to assing the lenght of a nullable variable to a non nullable, we can use an elvis to return a default one.

1val lenght: Int = s?.length ?: 0

to throw an esception from accessing an value of a null object, just use: person.company!!.address!!.country

but prefer explicit checks

Safe cast

a safe way to cast an expression to a type. In Java, you use a common pattern to do something with the variable only if it is of specific type. First, you use instanceof to check whether the variable is of the required type, then you cast it to this type of restoring the result in a new variable

Instead of using instanceOf or typeCast we can simply use is and as, but in the example, the as is not necessary

1if(any is String) {

2 val s = any as String

3 s.toUpperCase()

4}

Lambdas

Lambda is an anonymous function that can be used as an expression

1button.addActionListner{ println("H1") }

> we can store a lambda into a function val sum = { x:Int, y:Int -> x+y } But we can't store a function in a variable

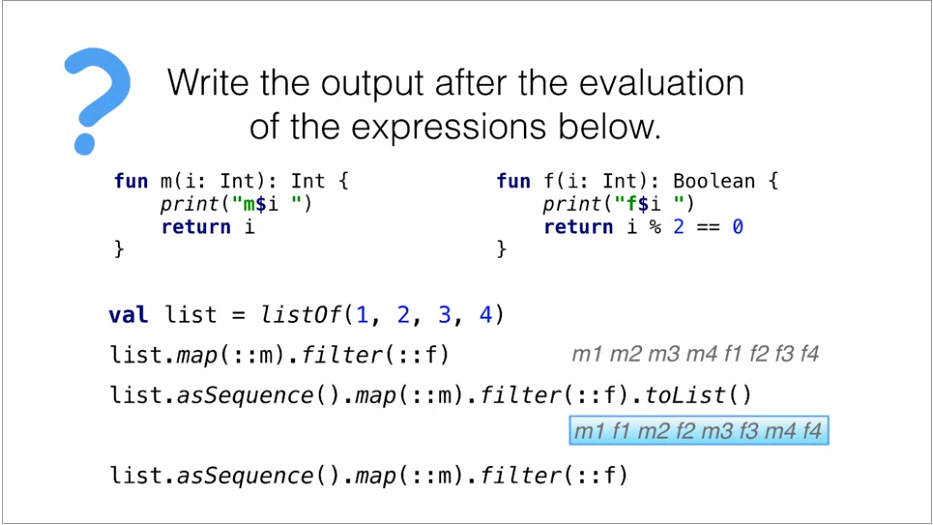

Sequences

filters and maps returns new values of a list, to avoid it we can use sequences, that are the same as stream

> Stream or sequences: If we use operations on collections, they eagerly return the result, while the operations on sequences postponed the actual computation, and therefore avoid creating intermediate collections.

1val list = listOf(1,2,-3)

2val maxOddSquare = list

3.asSequence() // same as .stream()

4.map{ it * it}

5.filter {it % 2 == 1}

6.max()

Generating a sequence

If you need to build a sequence from scratch, for instance, you define a way to receive each new element from the network, you can use the generateSequence function. Here, it generates a sequence of random numbers

1val seq = generateSequence {

2 Random.nextInt(5).takeIf { it > 0}

3}

4println(seq.toList())// [4,4,3,2,3,2]

> The generateSequence function can be useful when you need to read input and stop when a specific string is typed.

1val input = generateSequence {

2 readLine().takeIf { it != "exit" }

3}

4println(input.toList())

5/*

6>> a

7>> b

8>> exit

9[a,b]

10*/

Generating an infinite sequence

In this case, we generate an infinite sequence of integer numbers. Note that because this sequence is computed lazily, it might be infinite. Nothing happens until you explicitly ask for it.

1val numbers = generateSequence(0) {it + 1}

2number.take(5).toList() // [1,2,3,4,5]

Yield

Yield allows you to yield elements in a custom way. The generic sequence functions that we saw before, are white constraint

1val numbers = sequence {

2 var x = 0

3 while(true) {

4 yield(x++)

5 }

6}

7numbers.take(5).toList() //[0,1,2,3,4,5]

lambda with receiver (DSL)

It might be considered as a union of two ideas of two other features: extension functions and lambdas.

1// lambda function

2val isEven: (Int) -> Boolean = { it%2 == 0 }

3// lambda with receiver

4val isOdd: Int.() -> Boolean = { this % 2 == 1 }

5

6// calling

7isEven(0)

81.isOdd()

Return from lambda

Why in Kotlin return returns from the outer function? Consider the following example when you have a regular for loop and inside this for loop you use return. Return simply returns from the function. If you convert the for loop to foreach, then you can't expect that return continue to behave in the same way.

1fun containsZero(list: List<Int>): Boolean {

2 list.forEach {

3 if (it == 0) return true //this return the FUNCTION not the lambda!

4 }

5 return false

6}

to return from the lambda we have to use the labels return syntax:

1list.flatMap {

2 if(it === 0) return@flatMap listOf<Int>()

3 listOf(it, it)

4}

By default, you can use the name of the function that calls this lambda as a label. but we customize it

1list.flatMap l@ {

2 if(it === 0) return@l listOf<Int>()

3 listOf(it, it)

4}

if this is a problem, we can use a function inside of a function like:

1fun duplicateNonZeriLocalFunctcion(list: List<Int>):List<Int> {

2 fun duplicateNonZeroElement(e: Int) :List<Int> {

3 if(e==0) return listOf()

4 return listOf(e,e)

5 }

6 return list.flatMap(::duplicateNonZeroElement)

7}

8println(duplicateNonZeriLocalFunctcion(listOf(3,0,5)))

9// [3,3,5,5]

Or using an anonymous funcion

1fun duplicateNonZeriLocalFunctcion(list: List<Int>):List<Int> {

2 return list.flatMap(fun (e) :List<Int> {

3 if(e==0) return listOf()

4 return listOf(e,e)

5 })

6}

7println(duplicateNonZeriLocalFunctcion(listOf(3,0,5)))

8// [3,3,5,5]

> The return from the lambda doesnt stop the loop, its like a continue

Destructing declarations

The same syntax was used to iterate over a map in a for loop, by assigning a key and a value to separate variables

EG:

1map.mapValues{ entry-> "${entry.key} = ${entry.value}!" }

can be declared as:

1map.mapValues{ (key, value) -> "${key} = ${value}!" }

2// or

3map.mapValues{ (_, value) -> "${value}!" }

Iterating over a list with index

Note that iterating over list with this index also works using destructuring declarations. With index, extension function returns a list of index to value elements.

1for((index, element) in list.withIndex()) {

2 println("$index $element")

3}

Destructing declarations & data classes

You can use any data class as the right-hand side for the destructuring declarations, since the necessary component functions are automatically generated for it

1data class Contact (

2 val name: String,

3 val email: String,

4 val phoneNumber: String

5)

6

7val (name, _, phoneNumber) = contact

Some different lambdas

- ►

partition: its the same as filter, but returns 2 lists: One that satisfies the predicate and another that don't

1val heroes = listOf(Hero("The Captain", 60, MALE),Hero("Lady Lauren", 29, FEMALE))

2val (youngest, oldest) = heroes.partition { it.age < 30 }

3oldest.size

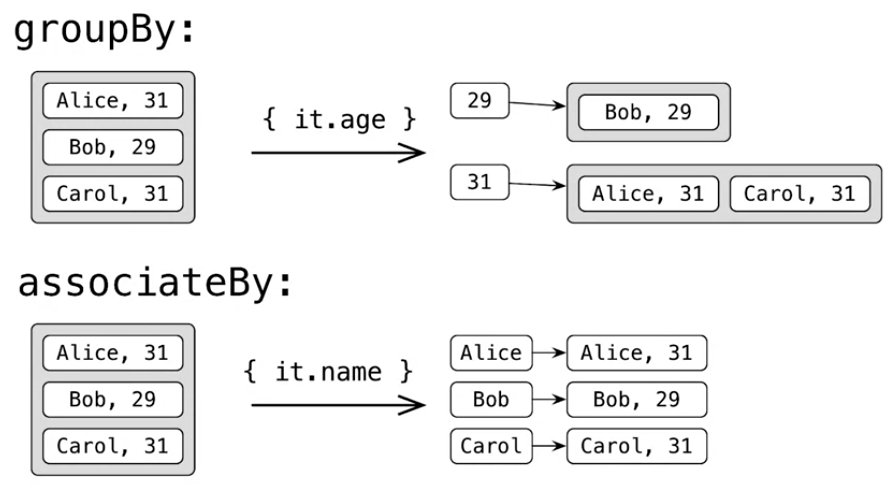

- ►

associateBy: the same as groupBy but removes the duplications, its a unique key, Eg:

1val heroes = listOf(Hero("The Captain", 60, MALE),Hero("Frenchy", 42, MALE),Hero("Sir Stephen", 37, MALE))

2val mapByName: Map<String, Hero> = heroes.associateBy { it.name }

3mapByName["Frenchy"]?.age

- ►

associate: Creates a pair over a list:listOf(1,2,3).associate{'a' + it to 10}that returns: a->10, b->20, c->30

1val heroes = listOf(Hero("The Captain", 60, MALE),Hero("Sir Stephen", 37, MALE))

2val mapByName = heroes.associate { it.name to it.age }

3mapByName.getOrElse("unknown") { 0 } //0

- ►

zip: returns a list of pair of 2 lists:

1val a = listOf(1,2,3);

2val b = listOf('a', 'b', 'c')

3a.zip(b)

4

5// 1->a, 2->b and 3->c

- ►

zipWithNextis the same as the zip, but it zips one list:listOf(1,2,3,4)would be: 1->2 3->4 - ►

flattencombine lists of lists into one list - ►

flatMapcan convert a string into a list of maps, and withflattenwe can merge then into 1 list - ►

filterValues: same as filter but for Pairs, ignoring the key - ►

taketakes only the fist x number of elements, like:incomeByDriver.take(topTwentyDrivers).sum() - ►

filterNotNullto remove null elements of a list - ►

maxBytakes the maximum using the predicate, like:

1val heroes = listOf(Hero("The Captain", 60, MALE), Hero("Frenchy", 42, MALE))

2heroes.maxBy { it.age }?.name

> Another interesting detail about maxBy, it can return more than one list

1val heroes = listOf(Hero("The Kid", 9, null),Hero("Lady Lauren", 29, FEMALE),Hero("First Mate", 29, MALE),Hero("Sir Stephen", 37, MALE))

2val mapByAge: Map<Int, List<Hero>> = heroes.groupBy { it.age }

3val (age, group) = mapByAge.maxBy { (_, group) -> group.size }!!

4println(age) // 29

Function types

parameter types are written inside the parentheses and then an arrow, then the return type. In this case, is the type that takes two integer parameters and returns an integer as a result.

as a lambda: val sum = { x:Int, y:Int -> x+y }

we can give it a type by:

1val sum: (Int, Int) -> Int = {x,y -> x+y}

Calling a stored function

You can call a variable a function type as a regular function, providing all the unnecessary arguments.

1val isEven: (Int) -> Boolean = {x:Int -> i%2 == 0}

2val result:Boolean = isEven(42) // true

3

4or as an lambda:

5listOf(1,2,3).any(isEven) // true

6list.filter(isEven) // [2,4]

We can run labdas by: {println("hey")}() or better: run {println("hey")}

SAM interfaces (Single abstract method invocations)

In Java, you can pass a Lambda instead of a SAM interface, an interface with only one single abstract method. In Kotlin, you can use the function types directly, but when you mix Kotlin and Java, you'd want to do the same as in Java. Whenever you call a method that takes SAM interface as a parameter, you can pass a Lambda as an argument to this method instead.

1void postponeComputation(int delay, Runnable computation)

2

3// SAM interface

4public interface Runnable {

5 public abstract void run();

6}

Whenever you call a method that takes SAM interface as a parameter, you can pass a Lambda as an argument to this method instead.postponeComputation(1000) {println(42)}

or if you want to use the constructor:

1val runnable = Runnable {printl(42)}

2postponeComputation(1000, runnable)

Nullable function type

The first one means that, return type is nullable. That's a possible mistake when you simply add a question mark after the function type. It means that you make the return type of this function type nullable, not the whole type itself. If you want to make the whole type nullable, you need to use the parentheses. In the example, you saw null in curly braces. It's a Lambda without arguments that always returns null.

1() ->Int? // return type is null

2(() -> Int)? // the variable is null

calling a null function

1val f: (()-> Int)? = null

2

3if(f != null) {

4 f()

5}

6// or safe call

7f?.invoke()

Member references

Like Java, Kotlin has member references, which can replace simple Lambdas that only call a member function or return a member property.

1class Person(val name: String, val age: Int)

2

3people.maxBy {it.age}

4// or

5people.maxBy(Person::age)

6// Person is the class

7// age is the member

if the reproached function takes several arguments, you have to repeat all the parameter names as Lambda parameters, and then explicitly pass them through, that makes this syntax robust. Member references allow you to hide all the parameters, because the compiler infers the types for you.

1val action = {person: Person, message: String -> sendEmail(person, message)}

2// same as

3val action = ::sendMail

Function references

If you try to assign a function to a variable, you'll get a compiler error. To fix this issue, use the function reference syntax. Function references allow you to store a reference to any defined function in a variable to be able to store it and qualitative it. Keep in mind that this syntax is just another way to call a function inside the Lambda, underlying implementation are the same.

1fun isEven(i:Int):Boolean = i%2==0

2val predicate = ::isEven

3// the same as

4val predicate = { i:Int -> isEven(i)}

Passing function references as an argument

whenever your Lambda tends to grow too large and to become too complicated, it makes sense to extract Lambda code into a separate function, then you use a reference to this function instead of a huge Lambda

1fun isEven(i:Int): Boolean = i%2==0

2val list = listOf(1,2,3,4)

3list.any(::isEven) // true

4list.filter(::isEven) [2,4]

Static and non static access:

1class Person(val name: String, val age: Int) {

2 fun isOlder(ageLimit:Int) = age > ageLimit

3}

4

5val agePredicate = Person::isOlder // non-bound or static

6val alice = Person("alice", 29)

7agePredicate(alice, 29) // true

8

9// bounded or non-static

10val alice = Person("Alice", 29)

11val agePredicate = alice::isOlder

12agePredicate(21) // true

13

14// and bound to this references

15class Person(val name: String, val age: Int) {

16 fun isOlder(ageLimit:Int) = age > ageLimit

17

18 fun getAgePredicate() = this::isOlder //we can ommit the this (::isOlder)

19}

Properties

Unlike Java where a property is not a language construct. Kotlin supports it as a separate language feature. In a most common scenario for a trivial case, property syntaxes are really concise. But you can customize it if needed

This is an customization of these field

1class Retangle(val height: Int, val width: Int) {

2

3 val isSquare: Boolean

4 get() {

5 return height == width

6 }

7}

8

9val rectangle = Rectangle(2,3)

10println(rectangle.isSquare) // false

Setting the field

In Kotlin, you don't work with fields directly, you work with properties. However, if you need, you can access a field inside its property accessors. It's not visible for other methods of the class.

1var state = false

2 set(value) {

3 print("setting state to $field")

4 field = value

5 }

Setter visibility

You can make a setter private. Then the getter is accessible everywhere. And therefore the property is accessible everywhere. But it's allowed to modify it only inside the same class. Note that we change only the visibility of the setter, but use the default implementation.

1var sample:Boolean = false

2private set

Property in interfaces

You can define a property in an interface. Why not? Under the hood, it's just a getter. Then you can redefine this getter in subclasses in the way you want.

1interface User {

2 val nickname: String

3}

4

5class FacebookUser(val accountId: Int): User {

6 override val nickname = getFacebookName(accountId)

7}

Extension properties

In Kotlin, you can define extension properties. The syntax is very similar to the one of defining extension functions.

1val String.lasIndex:Int

2 get() = this.length

3

4val String.indices: IntRange

5 get() = 0..lasIndex

6

7// "abc".lasIndex

Lazy property

Lazy Property is a property which values are computed only on the first success.

1val lazyValue: String by lazy {

2 println("computed")

3 "Hello"

4}

Lateinit: Late initialization

Sometimes, we want to initialize the property not in the constructor, but in a specially designated for that purpose method. Here, we initialized the myData property in onCreate method, but not in the constructor

1class KotlinActivity: Activity {

2 lateinit var MyData: MyData

3

4 fun create() {

5 myData = intent.getParcelableExtra("MY_DATA")

6 }

7}

OOP in Kotlin

🤨 Overall, Kotlin doesn't introduce anything conceptually new here, the experience is very similar.

| key | value |

|---|---|

| final | used by default, cannot be overridden |

| open | can be overridden |

| abstract | must be overridden, can't have an implementation |

| override | mandatory, overrides a member in a superclass or interface |

When you put val or var before the parameter, that automatically creates a property. Without val or var, it's on the constructor parameter.

1class Person(name: String) {

2 val name: String

3

4 init {

5 this.name = name

6 }

7}

8// or

9class Person(val name:String)

😀 You can hame multiple constructors, but each secondary constructor must call another secondary or primary constructor

1class Rectangle(val height: Int, val width: Int) {

2

3 constructor(side: Int) : this(side, side) {

4 }

5}

Enums class

The difference with Java is that now enum is not a separate instance, but a modifier before the class keyword.

1import Color.*

2

3enum class Color {

4 BLUE, ORANGE, RED

5}

6

7fun getDescription(color: Color) {

8 when(color) {

9 RED->"cold"

10 ORANGE -> "mild"

11 RED -> "hot"

12 }

13}

inner modifier

To access this reference of the outer class, you use labeled this. As the label name, you specify the name of the outer class.

1class A {

2 class B

3 inner class C {

4 ...this@A...

5 }

6}

Class delegation

In essence, class delegation allows you to delegate the task of generating trivial matters to the compiler. Note that the controller class implements both interfaces, so we can call interface members on it

1class Controller(

2 repository: Repository,

3 logger: Logger

4): Repository by repository, Logger by logger

Objects

The keyword object is a singleton in Kotlin: object K {fun foo() {}}; K.foo()

Objects Expressions replace java's anonymous classes:

1window.addMouseListner (

2 object: MouseAdapter() {

3 override fun mouseClicked(e: MouseEvent) {}

4 override fun mouseEntered(e: MouseEvent) {}

5 }

6)

Companion object

It's a nested object inside a class but a special one. The one which members can be accessed by the class name. In Kotlin, there are no static methods like in Java, and companion objects might be a replacement for that.

1class A {

2 companion object {

3 fun foo() = 1

4 }

5}

6fun main(args: Array<String>){

7 A.foo()

8}

Companion object can implment an interface

It would be nice if a static method could override a member of an interface. But for static, that's not possible in java. Now, it's possible for companion object.

1interface Factory<T> {

2 fun create():T

3}

4class A{

5 private constructor()

6 companion object : Factory<A> {

7 override fun create(): A {

8 return A()

9 }

10 }

11}

companion object can be a receiver of an extension function

Another thing which you can do with companion object, is you can define extension straight. To distinguish an extension to a class from an extension to a companion object, you use the companion suffix.

1class Person(val firstName: String, val lastName: String) {

2 companion object{...}

3}

4

5fun Person.Companion.fromJson(json: String): Person {

6...

7}

8

9val p = Person.fromJSON(json)

Generics

You define a type parameter for a function and try to use this type parameter in the function declaration, into the function body. You can call a generic function on different types.

1fun <T> List<T>.filter(predicate: (T)-> Boolean): List<T>

Non-nullable upper bound

If you want to restrict the generic argument so that it was not nullable, you can specify a non-null upper bound. You add an upper bound right after the type parameter declaration using the same column which replaces the extents cube root in Kotlin

1fun <T: Any> foo(list: List<T>) {

2 for(element in list) {}

3}

4

5foo(listOf(1, null)) // exception

Multiple constrains for a type parameter

Here, you can pass any type that extends to different interfaces, terrace sequence and aboundable. Stringbuilder implements both terrace sequence and dependable, so it's a valid argument for these function.

1fun <T> ensureTrailingPeriod(seq: T)

2 where T: CharSequence, T: Appendable {

3 if(!seq.endsWith('.')) {

4 seq.append('.')

5 }

6}

7

8val helloWorld = StringBuilder("Hello, World")

9ensureTrailingPeriod(helloWorld)

10println(helloWorld) // "Hello, World.

Conventions

accessing map elements using square brackets, actually work via conventions, and the same syntax might be supported for your custom process.

Arithmetic operations

In Kotlin, you can use this syntax of arithmetic operations not only primitives or strings, but for custom types as well. You define a function, a member or an extension with a specific name and mark it as operator.

1// a + b -> a.plus(b)

2

3operator fun Poin.plus(other: Point): Point {

4 return Point(x + other.x, y + other.y)

5}

It's not that you can use any name. You can see the correspondence between the syntax and the operator name that allows you to use this syntax.

| expression | function name |

|---|---|

| a + b | plus |

| a - b | minus |

| a * b | times |

| a / b | div |

| a % b | mod |

And the unary operators:

| expression | function name |

|---|---|

| +a | unaryPlus |

| -a | unaryMinus |

| !a | not |

| ++a, a++ | inc |

| --a, a-- | dec |

> Unary operator is a function without arguments which we can call as an operator on this specified receiver.

Prefer val to var

assigning the value like the following will create a new list, like: list = list + 4

1var list = listOf(1,2,3)

2list += 4

Comparisons

Under the hood, the comparison operators are all compiled using the comparative method comparisons.

| symbol | translate to |

|---|---|

| a > b | a.compareTo(b) > 0 |

| a < b | a.compareTo(b) < 0 |

| a >= b | a.compareTo(b) >= 0 |

| a <= b | a.compareTo(b) <= 0 |

Accessing elements by index: []

Under the hood, the get and set methods are called

1map[key]

2mutableMap[key] = newValue

3

4// is translate to

5x[a,b] -> x.get(a, b)

6x[a,b] = c -> x.set(a,b,c)

You can define get and set operator functions as members or extensions for your own custom classes.

1class Board {}

2board[1,2] = 'x'

3board[1,2] // x

4

5operator fun Board.get(x: Int, y: Int): Char {...}

6operator fun Board.set(x: Int, y: Int) {...}

The iterator convention

For loop iteration also goes through a convention. In Kotlin, you can iterate over a string.

1operator fun CharSequence.iterator() : CharIterator

2for(c in "abc"){}

Exams and tests

Every week we have an exame, these are the projects solving them:

- ► Week 2 Exam: Mastermind

- ► Week 3 Exam: Nice String and Taxi Park

- ► Week 4 Exam: Rationals and Board

- ► Week 5 Exam: Games

Week 2 exame: The Secret game

1data class Evaluation(val rightPosition: Int, val wrongPosition: Int)

2

3fun evaluateGuess(secret: String, guess: String): Evaluation {

4 val totalSecret: MutableList<Pair<Int, Char>> = secret.subtract(guess)

5 val totalGuess: MutableList<Pair<Int, Char>> = guess.subtract(secret)

6

7 return Evaluation(

8 rightPosition = calculateRightGuess(secret, totalSecret),

9 wrongPosition = calculateWrongPositions(totalSecret, totalGuess)

10 )

11}

12

13private fun calculateRightGuess(secret: String, totalSecret: MutableList<Pair<Int, Char>>) = secret.length - totalSecret.size

14private fun calculateWrongPositions(totalSecret: MutableList<Pair<Int, Char>>, totalGuess: MutableList<Pair<Int, Char>>): Int {

15 var wrong = 0

16 totalSecret.forEach {

17 val found = totalGuess.findChar(it.second)

18 if (found != null) {

19 wrong++

20 totalGuess.remove(found)

21 }

22 }

23 return wrong

24}

25

26private fun String.asIndexMap() = this.toCharArray().mapIndexed { index, c -> index to c }.toMutableList()

27private fun String.subtract(from: String) = this.asIndexMap().minus(from.asIndexMap()).toMutableList()

28private fun MutableList<Pair<Int, Char>>.findChar(needle: Char) = this.find { it.second == needle }

Kotlin Playground: Interchangeable predicates

Functions 'all', 'none' and 'any' are interchangeable, you can use one or the other to implement the same functionality. Implement the functions 'allNonZero' and 'containsZero' using all three predicates in turn. 'allNonZero' checks that all the elements in the list are non-zero; 'containsZero' checks that the list contains zero element. Add the negation before the whole call (right before 'any', 'all' or 'none') when necessary, not only inside the predicate.

1fun List<Int>.allNonZero() = all { it != 0 }

2fun List<Int>.allNonZero1() = none { it == 0 }

3fun List<Int>.allNonZero2() = !any { it == 0 }

4

5fun List<Int>.containsZero() = any { it == 0 }

6fun List<Int>.containsZero1() = !all { it != 0 }

7fun List<Int>.containsZero2() = !none { it == 0 }

8

9fun main(args: Array<String>) {

10 val list1 = listOf(1, 2, 3)

11 list1.allNonZero() eq true

12 list1.allNonZero1() eq true

13 list1.allNonZero2() eq true

14

15 list1.containsZero() eq false

16 list1.containsZero1() eq false

17 list1.containsZero2() eq false

18

19 val list2 = listOf(0, 1, 2)

20 list2.allNonZero() eq false

21 list2.allNonZero1() eq false

22 list2.allNonZero2() eq false

23

24 list2.containsZero() eq true

25 list2.containsZero1() eq true

26 list2.containsZero2() eq true

27}

28

29infix fun <T> T.eq(other: T) {

30 if (this == other) println("OK")

31 else println("Error: $this != $other")

32}

Assignment: Nice Strings

Nice String

A string is nice if at least two of the following conditions are satisfied:

- ► It doesn't contain substrings bu, ba or be;

- ► It contains at least three vowels (vowels are a, e, i, o and u);

- ► It contains a double letter (at least two similar letters following one another), like b in "abba".

Your task is to check whether a given string is nice. Strings for this task will consist of lowercase letters only. Note that for the purpose of this task, you don't need to consider 'y' as a vowel.

Note that any two conditions might be satisfied to make a string nice. For instance, "aei" satisfies only the conditions #1 and #2, and ```"nn"` satisfies the conditions #1 and #3, which means both strings are nice.

Example 1

- ► "bac" isn't nice. No conditions are satisfied: it contains a ba substring, contains only one vowel and no doubles.

Example 2

- ► "aza" isn't nice. Only the first condition is satisfied, but the string doesn't contain enough vowels or doubles.

Example 3

- ► "abaca" isn't nice. The second condition is satisfied: it contains three vowels a, but the other two aren't satisfied: it contains ba and no doubles.

Example 4

- ► "baaa" is nice. The conditions #2 and #3 are satisfied: it contains three vowels a and a double a.

Example 5

- ► "aaab" is nice, because all three conditions are satisfied.

1val VOWELS = listOf('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

2val forbiddenWords = listOf("ba", "be", "bu")

3

4fun String.isNice(): Boolean {

5 var total = 0

6

7 val hasNotForbiddenWords = { input: String -> if (forbiddenWords.none{ input.contains(it)}) 1 else 0 }

8 val hasMoreThenThreeVOWELS = { input: String -> if (input.count(VOWELS::contains) >= 3) 1 else 0 }

9 val hasDoubleLetters = { input: String -> if (input.zipWithNext().count { it.first == it.second } > 0) 1 else 0 }

10

11 total += hasNotForbiddenWords(this)

12 total += hasMoreThenThreeVOWELS(this)

13 total += hasDoubleLetters(this)

14

15 return total > 1

16}

Assignment: Taxi park

1/*

2 * Task #1. Find all the drivers who performed no trips.

3 */

4fun TaxiPark.findFakeDrivers(): Set<Driver> = allDrivers.minus(trips.map { it.driver }.toSet())

5

6/*

7 * Task #2. Find all the clients who completed at least the given number of trips.

8 */

9fun TaxiPark.findFaithfulPassengers(minTrips: Int): Set<Passenger> {

10 val byPassenger = trips.map { it.passengers }

11

12 return allPassengers.filter {

13 byPassenger.count { trip -> trip.contains(it) } >= minTrips

14 }.toSet()

15}

16

17/*

18 * Task #3. Find all the passengers, who were taken by a given driver more than once.

19 */

20fun TaxiPark.findFrequentPassengers(driver: Driver): Set<Passenger> = trips

21 .filter { it.driver == driver }

22 .flatMap (Trip::passengers)

23 .groupBy { passenger -> passenger }

24 .filterValues {group -> group.size > 1 }

25 .keys

26

27/*

28 * Task #4. Find the passengers who had a discount for majority of their trips.

29 */

30private fun Passenger.hadMoreTripsWithDiscount(trips: List<Trip>): Boolean {

31 val totalRides = trips.filter { it.passengers.contains(this) }.map { it.discount }

32 val ridesWithoutDiscount = totalRides.filter(Objects::isNull).size

33 val ridesWithDiscount = totalRides.filter(Objects::nonNull).size

34

35 return ridesWithDiscount > ridesWithoutDiscount

36}

37

38fun TaxiPark.findSmartPassengers(): Set<Passenger> = allPassengers.filter { it.hadMoreTripsWithDiscount(trips) }.toSet()

39

40/*

41 * Task #5. Find the most frequent trip duration among minute periods 0..9, 10..19, 20..29, and so on.

42 * Return any period if many are the most frequent, return `null` if there're no trips.

43 */

44fun TaxiPark.findTheMostFrequentTripDurationPeriod(): IntRange? {

45 return trips

46 .groupBy{

47 val start = it.duration /10 * 10

48 val end = start + 9

49 start..end

50 }

51 .maxBy{(_,group) -> group.size}

52 ?.key

53}

54

55/*

56 * Task #6.

57 * Check whether 20% of the drivers contribute 80% of the income.

58 */

59fun TaxiPark.checkParetoPrinciple(): Boolean {

60 if(this.trips.isEmpty()) {

61 return false

62 }

63 val incomeByDriver = trips

64 .groupBy { it.driver }

65 .map { (_, tripsByDriver) -> tripsByDriver.sumDouble(Trip::cost)}

66 .sortedByDescending { it }

67

68 val topTwentyDrivers = (allDrivers.size * 0.2).roundToInt()

69 var income = incomeByDriver.take(topTwentyDrivers).sum()

70

71

72 val total = trips.sumByDouble(Trip::cost)

73 val percentage = income * 100 / total

74 return percentage >= 80

75}

Unstable val

Implement the property 'foo' so that it produced a different value on each access. Note that you can modify the code outside the 'foo' getter (e.g. add additional imports or properties).

1var foo: Int = 0

2 get():Int {

3 field += 1

4 return field

5 }

6

7fun main(args: Array<String>) {

8 // The values should be different:

9 println(foo)

10 println(foo)

11 println(foo)

12}

Rational Numbers

Your task is to implement a class Rational representing rational numbers. A rational number is a number expressed as a ratio n/d , where n (numerator) and d (denominator) are integer numbers, except that d cannot be zero.

1package rationals

2

3import java.math.BigInteger.ONE

4import java.math.BigInteger.ZERO

5import java.math.BigInteger

6

7class Rational(val numerator: BigInteger, val denominator: BigInteger) {

8

9 companion object {

10 private fun minCommonDivisor(denominatorA: BigInteger, denominatorB: BigInteger): BigInteger {

11 val maxCommonDivisor = denominatorA.gcd(denominatorB)

12 return denominatorA * (denominatorB / maxCommonDivisor)

13 }

14

15 fun toSameBase(first: Rational, second: Rational): Pair<Rational, Rational> {

16 val mmc = minCommonDivisor(first.denominator, second.denominator)

17

18 val firstEquivalentRational = Rational(first.toEquivalentNumerator(mmc), mmc)

19 val secondEquivalentRational = Rational(second.toEquivalentNumerator(mmc), mmc)

20

21 return firstEquivalentRational to secondEquivalentRational

22 }

23 }

24

25 fun toEquivalentNumerator(mmc: BigInteger) = this.numerator * (mmc / this.denominator)

26

27 /*

28 The denominator must be always positive in the normalized form.

29 If the negative rational is normalized, then only the numerator can be negative,

30 e.g. the normalized form of 1/-2 should be -1/2.wq

31 */

32 fun normalize(): Rational {

33 if (numerator == ZERO) return this

34

35 val maxDivider = numerator.gcd(denominator)

36 val normalized = Rational(

37 numerator = numerator / maxDivider,

38 denominator = (denominator / maxDivider).abs()

39 )

40

41 return when {

42 denominator < ZERO -> -normalized

43 else -> normalized

44 }

45 }

46

47 override fun toString(): String {

48 return when (denominator) {

49 ONE -> numerator.toString()

50 else -> "$numerator/$denominator"

51 }

52 }

53

54 override fun equals(other: Any?) = when (other) {

55 is Rational -> this.numerator == other.numerator && this.denominator == other.denominator

56 else -> super.equals(other)

57 }

58

59 override fun hashCode(): Int {

60 var result = numerator.hashCode()

61 result = 31 * result + denominator.hashCode()

62 return result

63 }

64

65 operator fun compareTo(rational: Rational): Int {

66 val (sameBaseThis, sameBaseTarget) = toSameBase(this, rational)

67

68 return when {

69 sameBaseThis.numerator > sameBaseTarget.numerator -> 1

70 sameBaseThis.numerator < sameBaseTarget.numerator -> -1

71 else -> 0

72 }

73 }

74

75 operator fun unaryMinus(): Rational {

76 return Rational(-numerator, denominator)

77 }

78

79 operator fun rangeTo(rational: Rational): Pair<Rational, Rational> {

80 return Pair(this, rational)

81 }

82

83 operator fun plus(target: Rational): Rational {

84 val (sameBaseThis, sameBaseTarget) = toSameBase(this, target)

85 return Rational(

86 numerator = sameBaseThis.numerator + sameBaseTarget.numerator,

87 denominator = sameBaseThis.denominator

88 ).normalize()

89 }

90

91 operator fun minus(target: Rational): Rational {

92 val (sameBaseThis, sameBaseTarget) = toSameBase(this, target)

93 return Rational(

94 numerator = sameBaseThis.numerator - sameBaseTarget.numerator,

95 denominator = sameBaseThis.denominator

96 ).normalize()

97 }

98

99 operator fun times(target: Rational) = Rational(

100 numerator = this.numerator * target.numerator,

101 denominator = this.denominator * target.denominator

102 ).normalize()

103

104 operator fun div(target: Rational) = Rational(

105 numerator = this.numerator * target.denominator,

106 denominator = this.denominator * target.numerator).normalize()

107}

108

109operator fun Pair<Rational, Rational>.contains(rational: Rational): Boolean {

110 return rational >= this.first && rational < this.second

111}

112

113fun String.toRational(): Rational {

114 return if (this.contains("/")) {

115 val (num, den) = this.split("/")

116 Rational(num.toBigInteger(), den.toBigInteger()).normalize()

117 } else {

118 Rational(this.toBigInteger(), ONE)

119 }

120}

121

122infix fun Number.divBy(first: Number) = Rational(this.toString().toBigInteger(), first.toString().toBigInteger()).normalize()

123

124fun main() {

125 val half = 1 divBy 2

126 val third = 1 divBy 3

127

128 val sum: Rational = half + third

129 println(5 divBy 6 == sum)

130

131 val difference: Rational = half - third

132 println(1 divBy 6 == difference)

133

134 val product: Rational = half * third

135 println(1 divBy 6 == product)

136

137 val quotient: Rational = half / third

138 println(3 divBy 2 == quotient)

139

140 val negation: Rational = -half

141 println(-1 divBy 2 == negation)

142

143 println((2 divBy 1).toString() == "2")

144 println((-2 divBy 4).toString() == "-1/2")

145 println("117/1098".toRational().toString() == "13/122")

146

147 val twoThirds = 2 divBy 3

148 println(half < twoThirds)

149

150 println(half in third..twoThirds)

151

152 println(2000000000L divBy 4000000000L == 1 divBy 2)

153

154 println("912016490186296920119201192141970416029".toBigInteger() divBy

155 "1824032980372593840238402384283940832058".toBigInteger() == 1 divBy 2)

156}

Board

Your task is to implement interfaces SquareBoard and GameBoard.

SquareBoard stores the information about the square board and all the cells on it. It allows the retrieval of a cell by its indexes, parts of columns and rows on a board, or a specified neighbor of a cell.

GameBoard allows you to store values in board cells, update them, and enquire about stored values (like any, all etc.) Note that GameBoard extends SquareBoard.

1data class Cell(val i: Int, val j: Int) {

2 override fun toString() = "($i, $j)"

3}

4

5enum class Direction {

6 UP, DOWN, RIGHT, LEFT;

7

8 fun reversed() = when (this) {

9 UP -> DOWN

10 DOWN -> UP

11 RIGHT -> LEFT

12 LEFT -> RIGHT

13 }

14}

15

16interface SquareBoard {

17 val width: Int

18

19 fun getCellOrNull(i: Int, j: Int): Cell?

20 fun getCell(i: Int, j: Int): Cell

21

22 fun getAllCells(): Collection<Cell>

23

24 fun getRow(i: Int, jRange: IntProgression): List<Cell>

25 fun getColumn(iRange: IntProgression, j: Int): List<Cell>

26

27 fun Cell.getNeighbour(direction: Direction): Cell?

28}

29

30interface GameBoard<T> : SquareBoard {

31

32 operator fun get(cell: Cell): T?

33 operator fun set(cell: Cell, value: T?)

34

35 fun filter(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Collection<Cell>

36 fun find(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Cell?

37 fun any(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Boolean

38 fun all(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Boolean

39}

40

41open class SquareBoardImp(final override val width: Int) : SquareBoard {

42

43 private val cells: List<Cell> = sequence {

44 var i = 0

45 repeat(width) {

46 var j = 0

47 i++

48 repeat(width) {

49 j++

50 yield(Cell(i, j))

51 }

52 }

53 }.toList()

54

55 private fun List<Cell>.find(i: Int, j: Int) = this.find { it.i == i && it.j == j }

56

57 override fun getAllCells(): Collection<Cell> {

58 return cells

59 }

60

61 override fun getCell(i: Int, j: Int): Cell = cells.find(i, j)!!

62

63 override fun getCellOrNull(i: Int, j: Int): Cell? = cells.find(i, j)

64

65 override fun getColumn(iRange: IntProgression, j: Int): List<Cell> {

66 return sequence {

67 for (i in iRange) {

68 getCellOrNull(i, j)?.let { yield(it) }

69 }

70 }.toList()

71 }

72

73 override fun getRow(i: Int, jRange: IntProgression): List<Cell> {

74 return sequence {

75 for (j in jRange) {

76 getCellOrNull(i, j)?.let { yield(it) }

77 }

78 }.toList()

79 }

80

81 override fun Cell.getNeighbour(direction: Direction): Cell? {

82 val (i, j) = when (direction) {

83 Direction.UP -> i - 1 to j

84 Direction.DOWN -> i + 1 to j

85 Direction.RIGHT -> i to j + 1

86 Direction.LEFT -> i to j - 1

87 }

88 return cells.find(i, j)

89 }

90}

91

92class GameBoardImp<T>(size: Int) : SquareBoardImp(size), GameBoard<T> {

93

94 private var values: Set<Pair<Cell, T?>> = this.getAllCells().map { it to null }.toSet()

95

96 override fun get(cell: Cell): T? = values.find { it.first == cell }!!.second

97

98 override fun set(cell: Cell, value: T?) {

99 values = values.map {

100 val updatedValue = if (it.first == cell) value else it.second

101

102 it.first to updatedValue

103 }.toSet()

104 }

105

106 override fun filter(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Collection<Cell> {

107 return values.filter { predicate(it.second) }.map { it.first }

108 }

109

110 override fun find(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Cell? {

111 return values.find { predicate(it.second) }?.first

112 }

113

114 override fun any(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Boolean {

115 return values.any { predicate(it.second) }

116 }

117

118 override fun all(predicate: (T?) -> Boolean): Boolean {

119 return values.all { predicate(it.second) }

120 }

121}

Fibonacci sequence

Implement the function that builds a sequence of Fibonacci numbers using 'sequence' function. Use 'yield'.

1fun fibonacci(): Sequence<Int> = buildSequence {

2 val elements = Pair(0,1)

3 while(true) {

4 yiled(elements.first)

5 elements = Pair(elements.second, elements.first + elements.second)

6 }

7}

8

9fun main(args: Array<String>) {

10 fibonacci().take(4).toList().toString() eq

11 "[0, 1, 1, 2]"

12

13 fibonacci().take(10).toList().toString() eq

14 "[0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34]"

15}

16

17infix fun <T> T.eq(other: T) {

18 if (this == other) println("OK")

19 else println("Error: $this != $other")

20}